[ad_1]

“Will you take the coronavirus shot?”

While the camera was a bit out of place in the barbershop, the client was still casual and candid when he responded, “I don’t feel as though it’s safe. I’m saying, we don’t know if the medical administrators are telling us the truth about this thing. I mean, who knows what’s in this thing?”

His answer, along with a few others, was put together in the short video “Voices from the Barbershop: Coronavirus Vaccine Edition,” where everyday men answered the simple question to help inform public health officials of hesitations among the black community.

While the initiative is part of an established collaboration between black barbershops and public health helmed by Stephen Thomas, PhD, it’s also one of the many efforts aimed at increasing COVID vaccine uptake among black people. Thomas is the director of the Maryland Center for Health Equity at the University of Maryland.

Table of Contents

Contending with a history of racism

Studies have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affects black people and other minorities in the United States in severity, mortality, economics, and more. Thomas says, however, that it was just last summer when the New York Times had to sue the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to get a breakdown of infections by race. And a year ago some people even thought blacks were immune to the virus because of the melanin in their skin.

As Joe Smyser, PhD, MSPH, CEO of the health communications firm Public Good Projects, puts it, “Everybody knows about Tuskegee. Everybody knows about Henrietta Lacks. What I don’t often hear acknowledged is that the systemic racism that encouraged these two unethical, horrible incidents is still causing unethical, horrible incidents.”

Smyser points to a 2020 study that found black babies are three times more likely to survive if they’re cared for by a black physician than a white one. In 2010, he reminds, minority women were forced to be sterilized in the US prison system. And just 2 months ago, he says, Susan Moore, MD, a black physician, spoke about receiving racist treatment when she was hospitalized for COVID before succumbing to the infection.

Smyser points to a 2020 study that found black babies are three times more likely to survive if they’re cared for by a black physician than a white one. In 2010, he reminds, minority women were forced to be sterilized in the US prison system. And just 2 months ago, he says, Susan Moore, MD, a black physician, spoke about receiving racist treatment when she was hospitalized for COVID before succumbing to the infection.

Between mistrust, misinformation, and COVID management that has not always protected the most vulnerable (think inequitable test allocations and vaccination sites), how surprising is it that black communities have lower vaccine acceptance? And how can public health officials help change external factors and individual emotion to raise vaccine uptake?

Rising vaccine acceptance, but still lagging

According to Kaiser Family Foundation’s (KFF’s) Feb 1 statistics, which draw from 23 states, black and Hispanic people have received disproportionately fewer vaccine doses. In 20 of the states, the percentage of black people who received COVID vaccines is half or less than the proportion of black COVID cases.

Some of the greatest gaps are seen in Delaware (6% of vaccines received vs 24% of infections), Louisiana (13% vs 34%), Maine (1% vs 6%), Mississippi (17% vs 38%), and Pennsylvania (3% vs 14%). White people, on the other hand, have a higher number of vaccinated people than case percentages in all states but Alaska (28% vs 38%) and Nebraska (88% vs 89%).

Back in September, two polls shed some light on COVID beliefs and vaccine hesitancy. A KFF poll found that 85% of black people trust their own local doctor or healthcare provider, followed by the local health department (79%), the CDC (78%), and federal COVID lead Anthony Fauci, MD (77%). (Only 12% trusted then-President Donald Trump.)

Similarly, the COVID Collaborative reported black people had the highest levels of trust in their personal healthcare provider (72%) but found greater distrust toward Fauci (53%) and Trump (4%). The poll also indicated low levels of trust in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA; 29%), pharmacies and clinics (27%), and drug companies (19%).

Vaccine acceptance has risen since then, though. A January USA Today poll says 56% of Americans will get the vaccine as soon as they can, up 10 percentage points from the prior month (and up 30 from October 2020). The Harris Poll, as reported by Fierce Pharma, also showed an overall rise from 58% in October to 69% in January, with acceptance from black people increasing from 43% to 58%, respectively.

Still, public health advocates will have to communicate updates, correct misunderstandings, and manage expectations around vaccine side effects and distribution. Otherwise, as Thomas says, “It’s an activity in frustration. It’s good news, but they [black people] don’t know where to go; websites are breaking down. We’ve deferred maintenance in the public health infrastructure, and now we’re paying the price.”

Community efforts fill an outreach void

Thomas has been hoping to change community sentiment toward COVID-19 vaccines through his Health Advocates In-Reach and Research (HAIR) network, which has been going on for more than 5 years.

The HAIR network got its start training barbers from Prince George County, Maryland, to be lay health advocates for colorectal screenings. Since the pandemic, however, it has facilitated on-site COVID-19 testing services, conducted town halls to discuss the latest virus information, and implemented ultraviolet light fixtures to test their COVID mitigation efficacy.

“The health professionals, the epidemiologists, they obviously know more than the man on the corner, but you haven’t talked to the man on the corner in decades,” Thomas says. “We’ve been listening and helping people to take mitigation behaviors seriously.”

Thomas talks about how a health inspector came to one of the network’s barbershops and left a citation because one of the shop employees wasn’t wearing a mask. If the shop owner were not able to remedy the situation in a week, Thomas says, he would have been charged $1,000 a day. Then the inspector left without giving the owner masks, resources on where to find them for free or reduced prices, or even a fact sheet about why they were important.

“My point is we feel like we’re on our own, and if that’s the case, I want to build this barbershop health network as a real resource in not only addressing COVID but in addressing underlying health conditions that make African Americans so vulnerable to disease,” Thomas says.

In other parts of the United States, other black leaders are also advocating for COVID-19 vaccines. Florida’s Statewide COVID-19 Vaccine Community Engagement Task Force comprises black higher education representatives, business owners, media representatives, and politicians, and it was started not by the state government, but by R.B. Holmes, the pastor of Tallahassee’s Bethel Missionary Baptist Church. (According to the Miami Herald, the task force’s focus on minority vaccine campaigns will work with, not against, Gov. Ron DeSantis’ efforts.)

Another example comes from the Twin Cities, home to one of the largest populations of Somali Americans, which has seen some of the state’s highest infection rates.

Before COVID-19 vaccinations were even on the table, Hassanen Mohamed and the eight other members of their multipronged community response team were disseminating grassroots information. Word-of-mouth promotion and a few Somali media spots let it be known that if you had questions about COVID-19 or were having difficulty navigating the hospitalization processes, you could call the personal phone numbers of team members and they would help you.

The community response team doesn’t operate in partnership with any other organizations, but it has met with several hospitals and other public health institutions to address cultural barriers and inequities.

“[The other members and I] thought if you’re educated, speak good English, work in healthcare, and are still having a hard time, how about someone who is not educated and this is their first time interacting with the healthcare system with this magnitude of decision making, you know?” Mohamed told CIDRAP News. “That’s where we came and saw there was a need for community with this kind of discussion.”

Mohamed says that while there are many individuals in the Somali community who believe in vaccinations, misinformation stemming from the disproportionately high rates of autism must be overcome. The best way? “Engagement, engagement, engagement,” he says.

“Information changes. People only pick up highlights of information,” he adds. “One person has some form of an adverse reaction, and they spread that information 10 times more than the one that says, ‘Hey, I took the vaccination and haven’t been infected for 6 months.’ Bad news travels fast.”

Misinformation presents a daily battle

The KFF reports that black adults get COVID-19 information mostly from network (68%), cable (65%), and local (59%) news as well as friends and family (48%). At the same time, however, the COVID Collaborative poll indicates that 31% of black people have little or no knowledge of how vaccines work and 41% have little or no knowledge about how vaccines are developed and tested.

This can contribute to vaccine hesitancy, but so does the FDA’s less-than-ideal transparency and consistency around COVID-19 drugs and therapeutics, as noted by the US Government Accountability Office’s November CARES audit.

“Since information flows so quickly between and among communities, it will be a challenge for health departments across the country to rapidly react and respond to misinformation and ensure that correct information is provided,” Kim Martin, MAT, BSN, RSN, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) director of immunization, says.

To combat this, Smyser’s Public Good Project created the COVID communications tracker Project RCAID with Zignal Labs in mid-March last year, which dovetailed with Project VCTR, the vaccine communications monitoring program that the Public Good Projects already had. RCAID (short for Rapid Collection Analysis Interpretation and Dissemination) helps stakeholders monitor media stories, misinformation, and relevant topics related to COVID-19 across general and targeted populations.

To combat this, Smyser’s Public Good Project created the COVID communications tracker Project RCAID with Zignal Labs in mid-March last year, which dovetailed with Project VCTR, the vaccine communications monitoring program that the Public Good Projects already had. RCAID (short for Rapid Collection Analysis Interpretation and Dissemination) helps stakeholders monitor media stories, misinformation, and relevant topics related to COVID-19 across general and targeted populations.

“From what we see, most of [the misinformation] is the result of honest confusion and an earnest attempt to find good information,” Smyser says. “That said, we’re talking about millions of pieces of information created every day, seen billions of times. There is a whole lot that is maliciously created for money and influence.”

Local, national campaigns both needed

Public health and communication experts say that COVID information needs to have consistent strategy and messaging across all levels of governance.

“State and territorial health departments have strong partnerships with community organizations and engage with community leaders on a regular basis. Therefore, as trusted health experts, they are perfectly positioned to work with these partners in an inclusive manner to provide information, build trust, and increase collaboration,” says ASTHO’s Martin.

The Michigan Health and Human Services (MHHS) Department, for instance, has made partnerships across the state to understand the needs of all communities—and all diverse black communities. “It’s important to really work with the people on the ground and from the communities,” Joneigh Khaldun, MD, MPH, chief medical executive and chief deputy director of MHHS, says. “What’s needed in Detroit is very different than what’s needed in the Upper Peninsula.”

In some ways, what MHHS has done for the COVID-19 vaccine—building on relationships with community leaders, facilitating town halls and op-eds—is simply an expansion of the equity tactics the department used early on the pandemic.

In April 2020, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer created an interdisciplinary task force to address COVID disparities. (Khaldun says Michigan was one of the first states to do so; President Joe Biden signed in an executive order calling for a COVID-19 equity task force just last month.)

Besides working with community leaders and organizations, the Michigan task force helped guide targeted media messages, prioritize and expand testing resources, support worker quarantine, and distribute free masks and healthy food boxes. Healthcare providers also underwent mandatory bias training and used a new assessment tool to analyze health equity.

At least from August to October 2020, black COVID cases and deaths in the state were at the same rates or lower than their white counterparts.

Khaldun says, “I think the biggest challenge really has been when you don’t have a national strategy and you don’t have clarity or transparency on the supply chain, whether it be for testing or [personal protective equipment] or for vaccines, or just a consistent message from the national level. It makes it all the more difficult for faith at the local level.”

Addressing hesitation at clinics

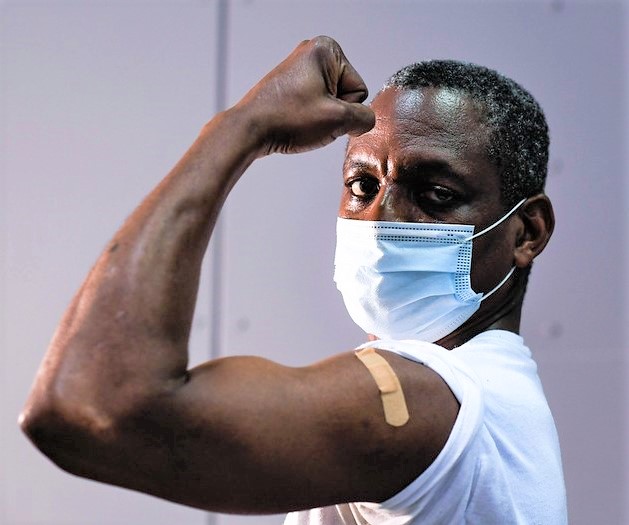

As COVID-19 vaccines make their way down the supply chain in increasing numbers, more and more people will find themselves going to clinics, pharmacies, sports arenas, and other traditional or nontraditional sites to receive them. That’s why it’s so important that even at this final step, any vaccine hesitation is met with empathy, not shame.

Minnesota Community Care, a nonprofit clinic that serves all people regardless of income, has been administering COVID-19 vaccines to those 65 and above since the end of January. It has also been doing its own outreach.

Through a partnership with Minnesota’s Community-University Health Care Centers, the staff has created videos and flyers to dispel COVID-19 myths. Some of the social media videos have featured healthcare providers giving testimonials about the vaccine; more than 74% of Minnesota Community Care’s healthcare workers are currently vaccinated. Rotating presentation slides in the clinic building go over vaccine facts, and deliberate effort is made to get information in front of populations that aren’t as reachable by social media, such as homeless people.

“We are working together to be able to have conversations that [may be] uncomfortable, to talk about things people are experiencing but not dismissing those experiences,” says Cindy N. Kaigama, MA, health equity design partner, adding that these dialogues are necessary to build trust.

Whether it’s discussing vaccine testing or acknowledging how pharmaceutical corporations could stand to profit from the pandemic, Kaigama says their healthcare workers will meet people where they’re at.

According to Kaigama, Minnesota Community Care’s patients cover the spectrum of vaccine hesitancy/acceptance, but even then, patients don’t always fit into one category. Kaigama recalls that one Nigerian family came in after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine from another provider despite having a discouraging social circle and not necessarily trusting the vaccine themselves. They were tired of living in fear.

To best serve them, the Minnesota Community Care healthcare worker went over the remaining questions the family had as well as possible side effects that might occur after the second dose.

“If [people] choose not to get the vaccination, we respect that as well,” Kaigama says, noting that hesitation has been seen across all demographics. “We need to be gentle with ourselves and make the best decision that works for us and our family.”

When black people do decide they want a COVID-19 vaccine, they should be able to get it without trouble, Thomas says. “We have to learn the lesson of Tuskegee and do everything in our power to ensure African Americans get the vaccine.”

Thomas talks of the three ethical principles that Tuskegee violated: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. With this last one, those who have the burden—of studies, of disease—should be the first to receive the benefit, he says. “I’d argue with you that black people, from the time of slavery to today, bore the burden. Now it’s time they get the benefit.”

[ad_2]

Source link