[ad_1]

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

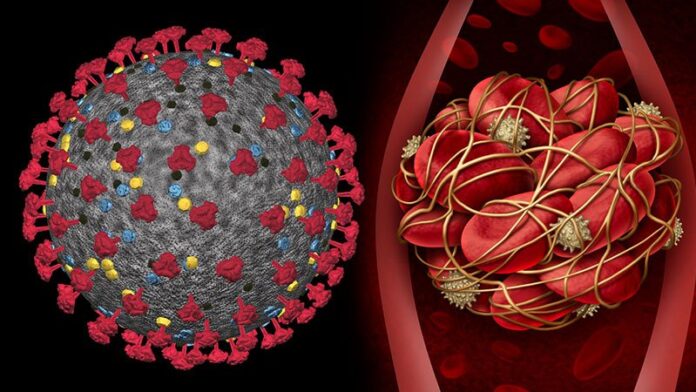

Early initiation of prophylactic anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients newly admitted to hospital appears to be associated with lower coronavirus disease mortality, compared with no treatment.

In an observational study of a cohort of patients receiving care in the Department of Veterans Affairs, those who received anticoagulation in the first 24 hours after hospital admission had a 27% lower risk for 30-day mortality than patients who received no anticoagulation therapy.

The study is published online February 11 in BMJ.

Christopher Rentsch

“We believe our work provides further evidence that initiating prophylactic doses of anticoagulation in earlier stages of severe COVID-19 provides greater benefit than initiating prophylactic or even full-dose anticoagulation when critically ill,” lead author Christopher T. Rentsch, MD, assistant professor of pharmaco-epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, and an investigator at the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, West Haven, Connecticut, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The study examined 4297 patients (median age, 68 years; 93% men) who were admitted to Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals from March 1 to July 31, 2020 with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection, and no history of anticoagulation.

Of these, 3627 (84.4%) received prophylactic anticoagulation within 24 hours of admission. All but 27 patients received subcutaneous heparin or enoxaparin.

Within 30 days of hospital admission, there were 622 deaths (14.5%).

Using inverse probability of treatment analyses, the researchers found that the cumulative incidence of mortality at 30 days was 14.3% (95% CI, 13.1% – 15.5%) among patients who received prophylactic anticoagulation, compared with 18.7% (95% CI, 15.1% – 22.9%) among those who did not, for a relative risk reduction as high as 34.0% and an absolute risk reduction of 4.4%.

Compared with patients who did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation, those who did had a 27% decreased risk for 30-day mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.73; 95% CI, 0.66 – 0.81).

Prophylactic anticoagulation was also associated with a 31% reduced risk for inpatient mortality (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.61 – 0.77) and a 19% reduced risk for initiation of therapeutic anticoagulation (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73 – 0.90).

There was no increased risk of bleeding that required transfusion among patients who received prophylactic anticoagulation (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.71 – 1.05).

“The results from this study are strikingly similar to the results of our observational study,” Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, director, Mount Sinai Heart, and physician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York CIty, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

That study, previously reported, looked at 4389 patients (median age, 65 years; 44% female) who were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Mount Sinai Health System between March 1 and April 30, 2020.

Of these patients, 1530 (34.9%) received no anticoagulation, 900 (20.5%) received therapeutic anticoagulation, and 1959 (44.6%) received prophylactic anticoagulation.

The data showed that patients on either therapeutic or prophylactic anticoagulation had roughly a 50% higher chance of survival than patients on no anticoagulation.

In January, the World Health Organization recommended the use of low-dose anticoagulation, although based on “very low certainty evidence,” and stated that higher doses could lead to other problems.

In December 2020, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued a statement that it was pausing three studies that were investigating increased levels of anticoagulation in critically ill COVID-19 patients in intensive care for futility and safety concerns.

The trials involved are the REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC studies.

“The patients in these trials were very sick, and the message is that these patients should not be treated with anticoagulation, and I don’t disagree with that,” Fuster said.

“In the patient who is in the hospital but not in the intensive care unit, the incidence of hemorrhage is relatively low,” he added. “We show this in our published study. But we cannot say the same for critically ill patients hospitalized in intensive care. Bleeding increases when the patient goes into the ICU, and this is the group that we feel less excited to treat.”

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institutes of Health. Rentsch and Fuster report no relevant financial relationships.

BMJ. Published online February 11, 2021. Full text

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

[ad_2]

Source link