[ad_1]

When Stephen Harris first met Guns N’ Roses, they were unknown and penniless, backing up The Cult on tour. “I used to steal alcohol from our dressing room for them and get them extra guest passes so they could sell them for money,” he says. “Once in a while, some of them would sleep on the floor of my hotel room.” That may sound unbelievable now, but so do many things about Harris’s life.

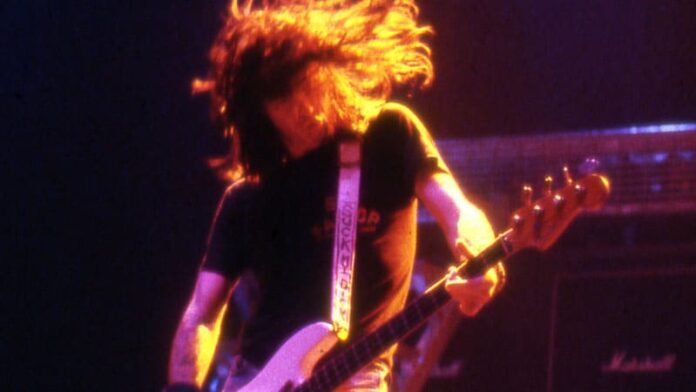

Stephen Harris at The Forum, Los Angeles, with The Cult in 1987.

Just 20 years old, he was playing sold-out concerts with The Cult at major venues around the globe. By age 26, he had left the music world behind and was studying to become a doctor. By age 47, a rare liver disease forced him to drop out of medical school. Now, at age 54, he is once again looking to help those struggling with illness. He’s helping oncologists develop a new resource for women battling ovarian cancer.

“I know, to some degree, how these women might feel,” Harris says. After stumbling into musical fame, Harris had completed 2 years of a medical degree at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York City, before having to leave school because of a rare illness. He hadn’t even known he was sick; a mandated screening as an incoming med student revealed that he had primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a condition he had never heard of.

Unexpected bumps in the road are all too common for Harris, whose unorthodox career has taken him from Swansea, in Wales, to New York City, Los Angeles, and around the world before finally bringing him back home to Swansea. His journey into medicine is equal parts tragedy, luck, persistence, and what Harris’s childhood friend James White calls “British bloody mindedness.”

Through it all, Harris’s fascinating, unconventional life story is filled with the very thing he now wants to provide to those coping with cancer: Hope.

Table of Contents

Early Tragedy and Unexpected Fame

Shortly after he turned 14, Harris’s mother and his 9-year-old sister were in a car accident. His mother was not expected to survive. She lived, but owing to the damage to her brain, “She was almost infantile,” said Harris. “She had trouble walking and talking and had no ability to attenuate her emotional response to things.” At the time, Harris and his family were living in Swansea. It was the early 1980s, and support such as counselors or social workers weren’t available. “We just carried on,” Harris said.

Not very interested in school, the teenaged Harris took refuge in music. A fan of punk rock and the proud owner of a bass guitar that his father bought him when he turned 11, Harris started living what he refers to as a “dual life.” He was both a dutiful son trying to help his family and obsessed with music. Then luck kicked in.

While visiting an old neighbor in London, Harris met the musician known as Youth, the former bass player for Killing Joke. He soon joined Youth’s band on stage. Then he met David Balfe of Food Records, which led Harris to the hard rock musician known as Zodiac Mindwarp, who just so happened to be looking for a bass player.

“I went home to my dad — my mother was ambulatory at this point — and said, ‘I am moving to London and I am joining a band,’ ” he said. At age 19, after about 6 months of playing shows without much attention, Zodiac Mindwarp and the Love Reaction, as the band was known, were written up in The Face, London’s trendsetting style and culture magazine.

“We went from being nothing to flavor of the year almost overnight,” Harris said. “The next thing I know, we had six major labels fighting in the dressing room.” Other trappings of rock stardom, including “girls camping in the front garden” and people recognizing him on the street.

“It was amazing,” said James White, who had been “joined at the hip” with Harris when they were growing up. “Stephen got an audition, went up to London, and then was off to the races.”

The races took another turn when Harris got an offer from The Cult. They invited him to play bass on a record they were recording in New York. Harris accepted. On January 3, 1987, the 20-year old found himself standing in Electric Lady Studios in New York with the band and their producer, a young Rick Rubin. Harris toured first with The Cult, playing sold-out concerts around the world, and then briefly with Guns N’ Roses, when they were supporting Iron Maiden. “It was a crazy time,” said Harris.

At the urging of Rubin, he moved to Los Angeles and formed his own band, The Four Horsemen. Harris played lead guitar and did his best to keep the band focused. Being a musician and a businessman at the same time took its toll.

In 1992, Harris decided it was time to leave the music industry. “I was 25 going on 26 and I was tired, really tired,” he said. He found himself back in Manhattan with no idea what to do with his life. “I didn’t know who I was or what I wanted to do.”

From Rock Music to Rock Climbing and Med School

Uncertain of his next move, Harris accompanied a friend to a gym that had a rock-climbing wall. Despite his initial reaction — “there’s no way I am doing that” — he discovered he had a natural talent for it.

After going to the gym obsessively for a while, he was offered a job as an instructor. About 8 months later, in 1999, Goldman Sachs came looking to hire trainers for a climbing wall at their private gym in the World Trade Center. Harris got the job.

Harris isn’t sure what he would have done had the world gone on as normal, but the long story short, as he puts it, was 9/11. He was fortunate to have not been at the Twin Towers that day. He became involved with rescue and cleanup efforts. “I was allowed to do something meaningful,” he said.

The only way in and out of Ground Zero took Harris past a community college. One day, he walked in and sat down with a student counselor named Nancy. “I filled in a form and looked at all the courses and there was a course for nursing that I was interested in,” said Harris. Nancy suggested medical school instead. Harris laughed at the idea.

“I’m 33 years old, and I haven’t been to school since I was a kid,” he told her. “If I go to med school, I won’t be a doctor until I am 43.” “You’ll be 43 anyway,” Nancy replied.

With that, Harris started an arduous path to medical school. He was soon diagnosed with a learning disability and won a scholarship to Columbia University, where he pursued his premed studies and an undergraduate degree in cultural anthropology. In the middle of his studies, Harris went to the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai to inquire about an early placement program in medicine and the humanities. “I never thought I would get in,” he said.

While looking for basic information, he soon found himself in front of not just any admissions officer but the head of the program, Miki Rifkin, PhD. While at the meeting, Harris realized that he was wearing a shirt with a baked bean stain on it. “I looked like I had been dragged through a hedge backwards,” he said. “I didn’t think I was going to be interviewed by anyone, I thought I was just going to have a chat about the program.”

After looking at his transcripts, Rifkin asked, “Why Mount Sinai? Why not somewhere else?” Harris’s response: “Everyone else is kind of like Joan Baez, but I feel like Mount Sinai is Joni Mitchell.”

“[Rifkin] looked at me and said, ‘Well, we closed applications 2 weeks ago, but if you fill this in, we’ll wait for you.'”

From Rock Music to Rock Climbing and Med School

As with so many things in his life, Harris’s studies did not go as planned. He was diagnosed with PSC the Friday before starting med school. In addition, he developed Crohn’s disease, which is commonly associated with PSC. It was initially resistant to treatment. When his health got too bad, Harris had to take time off. After 4 years, he had completed only 2 years of schooling and was running out of allowable leave. In 2014, at the age of 47, he withdrew from Mount Sinai.

“I had a vision, and I had a lot of people rooting for me,” he said. “Withdrawing made me feel like I was letting a lot of people down.” Two of the people who had rooted for him were Peter Dottino, MD, and Anne Marie Beddoe, MD, MPH. They had taken Harris under their wing when he started at Mount Sinai.

Anne Marie Beddoe, MD, MPH, (first from left), Peter Dottino, MD, (fifth from left), and Stephen Harris (sixth from left) in Liberia in 2008.

“I think anybody can learn something from Stephen’s story,” said Dottino, who is co-director of the Gynecologic Cancer Translation Research Program at Mount Sinai. Dottino helped found a program there that partners women diagnosed with gynecologic cancer with cancer survivors who have been trained to mentor them. He and Beddoe envisioned expanding the idea. They knew Harris was the perfect person to help them.

As one half of S2Motion, a small technology company, Harris helped the doctors develop the site Ovarian Cancer Stories, a collaboration with members of thewomen.org, which is designed to provide information and comfort to women who were recently diagnosed. By the time many of these patients see a specialist, “they have been on the internet, and they are basically writing their wills,” said Harris.

This was upsetting to Dottino and Beddoe. “In our practice, we had women who were surviving this disease,” said Dottino. “It was pissing us off that no one was putting out a word of hope for these patients.”

Together with Harris, they were determined to rectify that. Harris drew on his cultural anthropology background to help develop the questionnaires for survivors, and he conducted live interviews. He really put the patients at ease and got them to talk about difficult things, said Dottino. “He has an innate talent; I’m not sure he recognizes that.”

All three — Harris, Dottino, and Beddoe — are proud of the project and hope that it finds its way to women who need it. The site is searchable by patient, subject, and common keywords so that those who use it can find what they need when they need it. Now that they have a working model, Harris is in discussions to expand the project to other kinds of cancers.

Through this site or via other means, Harris says his calling is helping people. His own health has stabilized, and he is now back in Swansea, where he has been taking care of his elderly parents since the beginning of the pandemic. His father has lung problems, and his mother, as well as surviving the car accident, is a two-time breast cancer survivor.

Stephen Harris present day.

Harris says that seeing the National Health Service (NHS) overwhelmed and in need of doctors for the fight against COVID has given him another farfetched idea. He may just finish his medical schooling in order to help.

“It’s not really up to me,” he said when asked about the likelihood of his returning to med school. “Is there a need for a 54-year-old at that stage in training? Maybe there is, given the state of NHS. Would I do it? Yes, I think I would.”

He has only made what he calls “unofficial inquiries” at this point and knows it’s a long shot. Then again, long shots are kind of Harris’s thing. If his unconventional life story has shown him anything, it’s that there is always hope.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

[ad_2]

Source link